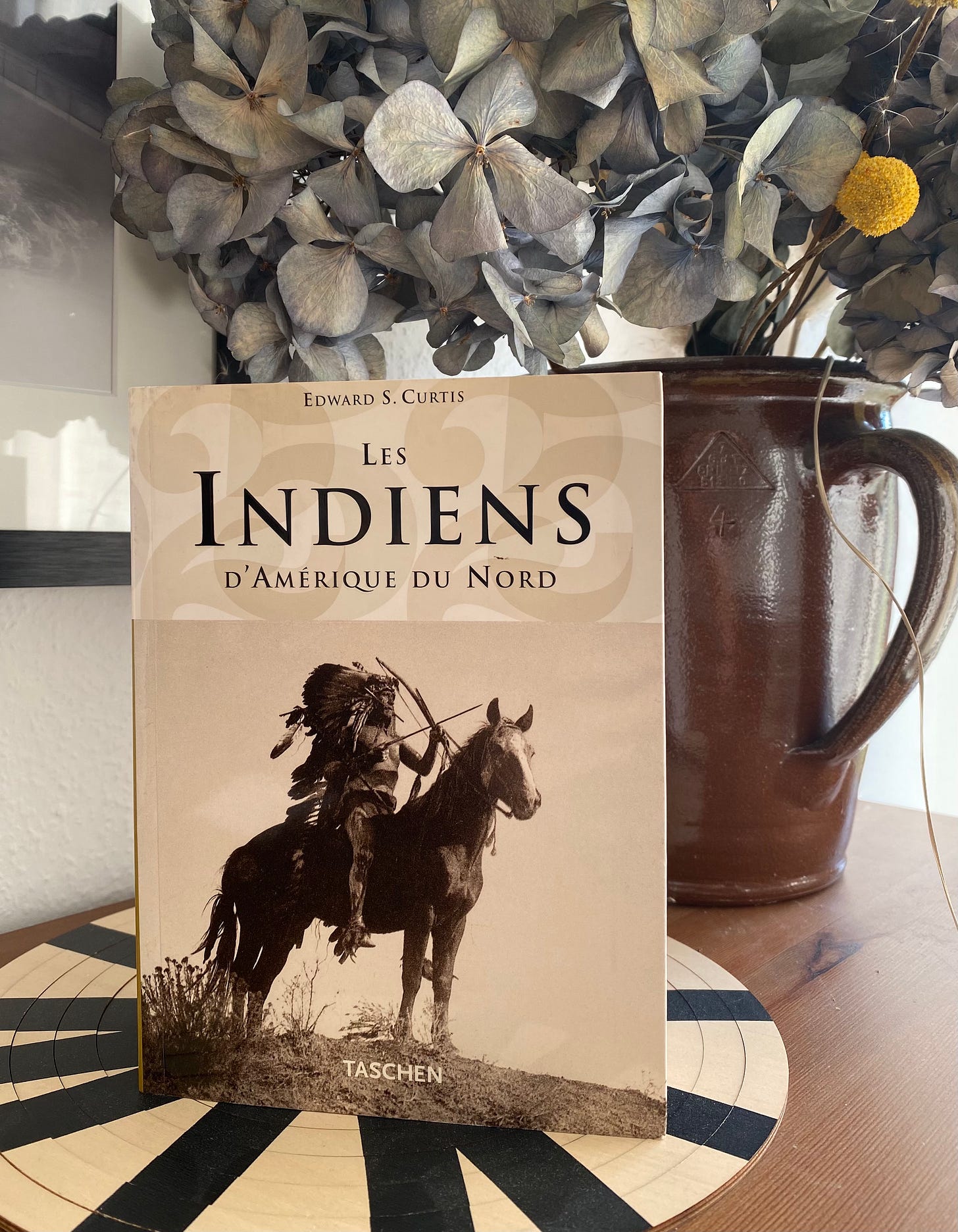

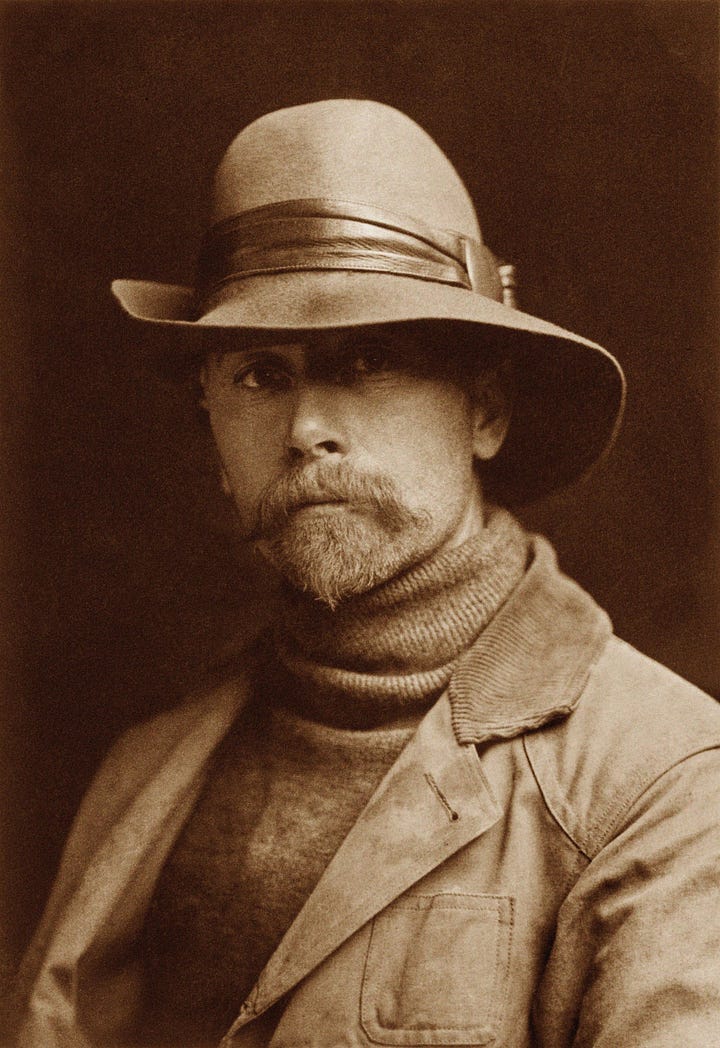

Another story starting in Paris. I guess fun things happen when you are on vacation. I was having dinner at my aunt’s flat and took a look at her library. My aunt and her husband used to be avid photographers, not professional but really good at taking candid shots. So their collection of photographic coffee table books are serious. I played a quick memory match game with the books and saw two of the same, Taschen’s The North American Indian by Edward Sheriff Curtis. Quite a sad irony that the photographer who shot these amazing people and sceneries carried the middle name of Sheriff (awkward cough.) They never noticed they had two of the same book, one in English and the other in French so they gifted me the french one. It’s a chunky book and my already filled to the brim backpack had to make room and keep it in pristine condition to bring it back home. Which I am glad to say that it did.

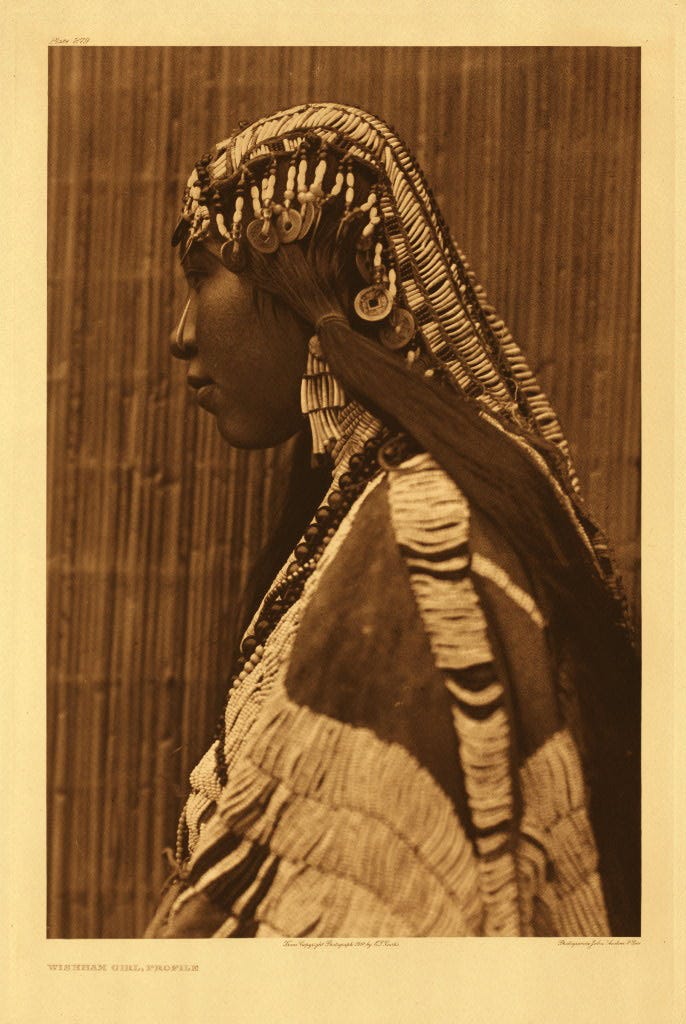

The pictures are breathtaking and I never understand how photographers capture such comfortable environments and emotions with their subjects. A sublime historical documentation of a time forgotten. This book shows you what to me feels like the real way to live on this planet, through respectfully living off the land and among a strong community and beautiful people if I might add. With one principle I remember well and love to bring into conversation to hear other’s opinion on is — The Seventh Generation Principle. A principle that is based on American Indian philosophy where, what will be the consequences or benefits of one serious decision in seven generations time. What an honourable way to live unselfishly and think for the future, truly. Which brings me back to talking about this principle among friends and the best debate I had about it had the notion of today it’s impossible to predict or imagine the future seven generations from now with technology and all that jazz. Fair point, but it’s still worth a try and maybe more important than ever.

Speaking of jazz, that’s what I was listening to while looking at the book portrayed like a painting on top of our bookshelf at home. Thinking to myself of the traditions and lifestyles of an American Indian. Then of course my mind/stomach gargled and I couldn’t help to think about their culinary history and what difference of diets each tribe had or the tribal culinary and cultural differences. What restrictions or rules did they live by in terms of gathering, growing, preparing and storing? Or more simply for me and easier to research (hopefully) what was a staple meal besides maize, beans and squash famously attributed to the American Indian.

I then remembered the Sioux Chef, Sean Sherman (what an amazing pun by the way.) He made it his life’s mission to promote, organise and address indigenous food access and education. He noticed the effects of colonial diets and produce such as dairy, sugar and flour on those who live on reservations, and the consequences thereof. Such as: diabetes, cancer, obesity and tooth decay to name a few. The effects of a Western diet doesn’t stop with American Indians, it goes further than that.

It reminds me of Weston Price, a Canadian dentist who traveled the world and studied diets and nutrition, after his theory of focal infections ( a concept of some infections causing chronic or acute diseases in other parts of the body) fell out of favour among dentists. I guess for redemption’s sake, he wrote his book Nutrition and Physical Degeneration. It explains what The Sioux Chef also noticed and is fighting against, how the modern Western diet causes health problems and tooth decay. Price’s proof was his ethnographical studies (which in itself, is an iffy and quite racist study) where he made nutritional studies among the Swiss, American Indians, Polynesians, Pygmies and Aborigines, and many more. His research was extensive with 15,000 photographs, and plenty more documentation. Quite obsessive in my opinion but if you take a look at some of his chapters it is a pretty impressive study. The difference between isolated communities compared to reservations or close contact with the white man ruined the health of many. You don’t need to travel the world and or take a deeper look into teeth to understand the Western diet isn’t the most healthy.

A similar adventuring anthropologist by the name of Colin Turnbull spent three years with the Mbuti pygmies of Eastern Congo in 1951. In his book The Forest People he describes how the Mbuti are at one with their surrounding, it sounds so similar to the way of life and resources respected by the American Indian. As said in this excerpt of the book selected in Sitopia by Carolyn Steel:

[…] the Pygmies have been in the forest for many thousands of years. It is their world, and in return for their affection and trust it supplies them with all their needs. They do not have to cut forest down to build plantations, for they know how to hunt the game of the region and gather wild fruits that grow in abundance there, though hidden to outsiders. […] they recognize the kind of weather that brings a multitude of different kinds of mushrooms springing to the surface; and they know what kinds of wood and leaves often disguise this food. [..] They know the secret language that is denied all outsiders and without which life in the forest is an impossibility.

Which is a bit off track, but I found that passage fitting to the American Indian lifestyle. Another and final tale of culinary innovation, like Sean Sherman is one from U.S. Chef Dan Barber and his epiphany from his restaurant Blue Hill at Stone Barns. He was sent a shriveled corncob in the post from a heritage seed collector with $1,000 cheque along a note asking to grow it. Dan Barber asked his vegetable growing expert Jack Algiere to try. He did use the Three Sisters method traditional to the Iroquois, planting it next to dry beans and squash. The corn would give support for the beans and the squash would inhibit weeds. Finally when Barber made polenta with that corn he states: “It wasn’t just the best polenta of my life […] it was polenta I hadn’t imagined possible, so corny […] the taste didn’t so much disappear as slowly, begrudgingly fade. It was an awakening.” He understood nature can give so much beyond crop, the cook, or the farmer and how it all fits together. Instead demanding nature what to supply we need to ask the landscape what it wants to grow. Kind of like asking a living breathing thing what it wants… you know?

I may be highlighting the extreme case of living within nature and what once was. Finding a way to revert to respecting food in its natural habitat or sharing forgotten knowledge is the work of a true historian. Sean Sherman fights his way for a healthy community, sharing knowledge of forgotten methods and crops to bring them back to life. He is an authority in American Indian food and has been accredited numerous awards. Time magazine dubbed him The 100 Most Influential People of 2023. His cookbook The Sioux Chef's Indigenous Kitchen won several awards among them a James Beard Award in 2018 for Best American Cookbook and he collected another in 2019 for the James Beard Leadership Award. His work grew to create a nonprofit called North American Traditional Indigenous Food Systems or NĀTIFS, which helps educate and support Indigenous food systems and provides resources to help people share common ground through food heritage. Finally, he co-founded the restaurant Owamni in Minneapolis.

On his Sioux Chef website, he has one of the most bad-ass mission statements which I would love to quote:

“We are a team of Anishinaabe, Mdewakanton Dakota, Navajo, Northern Cheyenne, Oglala Lakota, Wahpeton-Sisseton Dakota and are ever growing. We are chefs, ethnobotanists, food preservationists, adventurers, foragers, caterers, event planners, artists, musicians, food truckers and food lovers.

We are committed to revitalizing Native American Cuisine and in the process we are re-identifying North American Cuisine and reclaiming an important culinary culture long buried and often inaccessible.”

Somehow, whether The Sioux Chef knows it or not, I believe he is living by the Seventh Generation Principle and fighting for his culture and for those to come. This ambition of fighting for food justice and equity at the table is something I love to see and is just plain awesome. What else is there if we don’t uphold values for ourselves and for those we love. How noble to dive into your identity and share that with the world. To find and protect the initial ways of indigenous food. It’s protecting history, culture and the future. It’s humbling. I just felt the need to share that, and his story. Hopefully it will inspire.

Red beans and ricely yours,

The Greasy Pen.

P.S. Please don’t hesitate to leave a comment! I would love nothing more than to get in touch or continue the conversation.